Originally published January 24, 2014 by the US National Library of Medicine

Circulating Now welcomes guest bloggers Diane Wendt and Mallory Warner from the Division of Medicine and Science at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. As curators of our most recent exhibition, From DNA to Beer: Harnessing Nature in Medicine and Industry, Diane and Mallory spent months researching four different microbes and the influence they’ve had on human life. Beginning with this post they share some of the interesting things they found in their research.

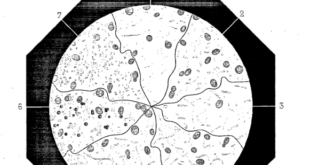

Among the four microbes featured in From DNA to Beer, the little one cell creature named yeast may be our favorite. In the exhibition, we focus on the role yeast played in the work of Louis Pasteur, namely how his research on the “diseases” of beer and other fermented products established yeast’s connection to the process of alcoholic fermentation which, in turn, inspired his germ theory of disease. In focusing our view, however, we had to leave out the following exciting finds about beer, yeast, and Louis Pasteur.

Pasteur studied beer to get revenge on Germany

Pasteur’s Études sur la bière (translated as, Studies on Fermentation: The Diseases of Beer, Their Causes, and the Means of Preventing Them), is celebrated for providing strong, elegant evidence dispelling spontaneous generation and for identifying the microbial causes of spoilage of beer. Having already studied “diseases” in wine, vinegar, and silkworms, as noted in this catalog for an exhibit on Pasteur, one might think beer was simply the next obvious problem product for Pasteur to fix. His introduction to Études, however, points to another reason for focusing on beer:

Our misfortunes inspired me with the idea of these researches. I undertook them immediately after the war of 1870, and have since continued them without interruption, with the determination of perfecting them, and thereby benefiting a branch of industry wherein we are undoubtedly surpassed by Germany.

Essentially, Pasteur funneled his anger over the French loss of the Franco-Prussian War into attacking that which Germany loves most: beer. He hoped increased knowledge about the science of beer brewing would put France in a position to best the German beer industry.

Yeast Advertising is… interesting

When considering whether to include some yeast-related objects in the exhibit, we delved into collections from several institutions. While none of these objects made it into the show, we couldn’t help but share a few here:

Pasteur had his own newspaper. Sort of.

One of our favorite finds from the NLM collection was this advertising newspaper, Le Pasteur, first published by the Pasteur-Chamberland Filter Company of Dayton Ohio in 1889. When looking for a means to sterilize water in the lab without boiling, Pasteur found that passing the water through an unglazed porcelain filter removed bacterial contaminants. His student, Chamberland, designed a filter using this principle and the result became an important tool not only in the lab, but for filtering everyday drinking water. To advertise the sale of their filters, the Pasteur-Chamberland Company (the American licensee of the Pasteur-Chamberland filter patent) published Le Pasteur, a newspaper full of product testimonials, glorious documentation of Pasteur’s achievements, and lists of the most recent establishments to purchase Pasteur-Chamberland filtration systems. Their over-dramatic sales tactics are endlessly entertaining. One delightful example of Le Pasteur’s hyperbole can be found in the first stanza of a 44-line poem “The Old Oaken Bucket,” published in the April 1889 edition. In it, the poet J. W. Bayles laments his childhood spent drinking well-water from a bucket, which he describes in disgusting detail.

“With what anguish of mind I remember my childhood,

Recalled in the light of knowledge since gained;

The malarious farm, the wet, fungus-grown wild-wood,

The chills then contracted which since have remained;

The scum-covered duck-pond, the pigsty close by it,

The ditch where the sour-smelling house drainage fell.

The damp, shaded dwelling, the foul barnyard nigh it—

But worse than all else was the terrible well.

And the old oaken bucket, the mold-crusted bucket,

The moss-covered bucket that hung in the well.”

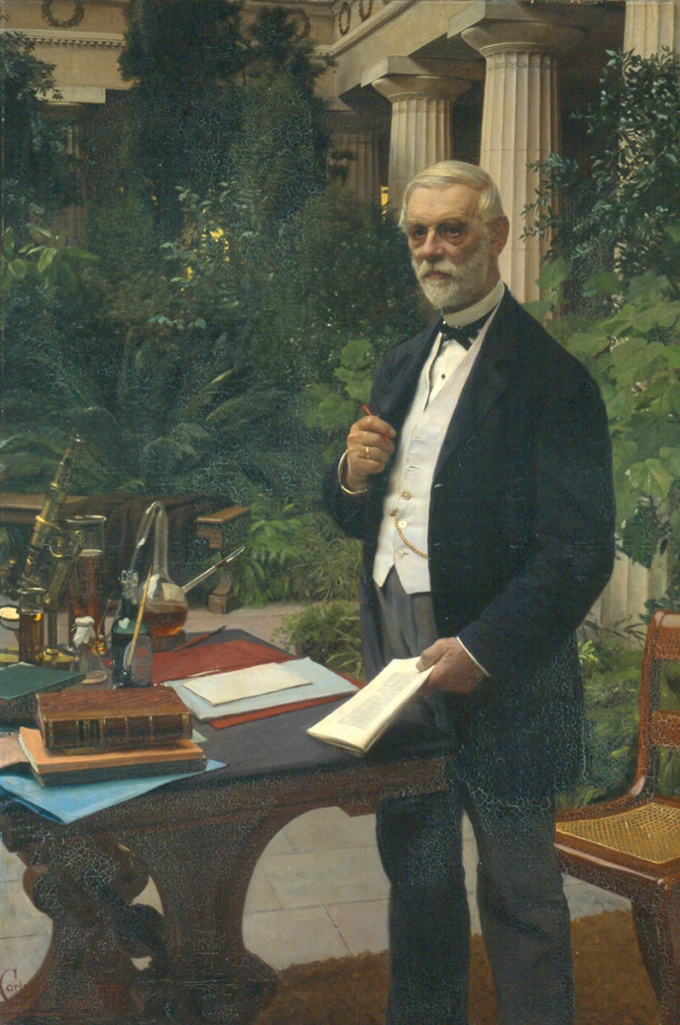

A Brewer’s Portrait Pays Homage to Pasteur

Jacob Christian Jacobsen, head of the Carlsberg brewery in Copenhagen, was an admirer of the work of Louis Pasteur. In 1875 he established the Carlsberg Laboratory for the scientific study of the brewing process. This portrait, painted the year before he died, features a microscope, Pasteur flask, and Pasteur’s book alongside a bottle of Carlsberg’s famous beer.

Courtesy Frederiksborg Museum

In the 1880s, Emil Hansen, a scientist at the laboratory, isolated a pure strain of yeast that was suitable for lager brewing. He named the yeast Saccharomyces carlsbergensis after the laboratory, and went on to isolate and identify numerous other strains of yeast including Saccharomyces pastorianus, named after Pasteur. And so the history of yeast science is embedded in the names given to this tiny organism responsible for much of the beer on the market. Today, the Carlsberg Laboratory remains an important center of yeast research.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing