According to almanac makers we shall shortly be passing through the dog days. The star “whose burning breath,” as Homer sang, “taints the red air with fevers, plagues and death,” will soon be in the ascendant, and, according to ancient faith, exerting its direful influence upon the creatures of this earth. Now should we give thoughtful heed to the kindly warnings of municipal authorities about muzzling and leading out canine dependents; and it may be that an occasional cry of “mad dog!” will during the warm weather strengthen the popular belief that the dog days are so called because dogs go mad during their course, and that hydrophobia is an evil effect for which the bright star in the constellation Canis Minor is somehow responsible. But with our thankful respect for the efforts of those gentlemen who compile our almanacs, we cannot help reminding them that the regular and exact entry of dog days in the calendars is highly discreditable to their knowledge, and that the belief that certain dates are favorable or conducive to the disturbance of canine sanity is by no means honorable to an age whose people are bristling with educational schemes.

Hydrophobia (Rabies) the Disease

The disease, as at present known, is always communicated by the bite of a rabid animal – usually a dog, but sometimes by a ct, wolf, fox, jackal, raccoon or even a badger, for all carnivorous animals are liable to rabies, and it is among them that it invariably originates. It is not many years since a death occurred in this city resulting from the bite of a cat, the feline and the victim exhibiting hydrophobic symptoms, and cases have been known where both horses and cattle have become afflicted with madness of an acute type. But to communicate the disease, the animal itself must be rabid when the bite is inflicted. The old superstition that if a man is bitten by a dog, and the dog afterward goes mad, the man is in danger of hydrophobia, is altogether absurd, and gives rise to much groundless alarm. We might as well suppose that if our friend leaves us for South America, and there dies of the yellow fever, we are ourselves in danger because we shook hands with him when he left New York. The bite of a dog is always an ugly, painful thing, and apt to fester and heal badly. But the bite of a dog in health cannot possibly give hydrophobia; the animal must itself be rabid, and under ordinary circumstances there is no ground for any grave apprehension on account of a bite, no matter how severe it may be. Even those who are bitten by a rabid dog will do well not to be seriously alarmed. In the first place the bite, even if not attended to, does not by any means always result in the disease. Statistics, indeed, would seem to show that the chances of escape are almost as five to two, only forty deaths occurring out of a hundred persons bitten. But beside this original chance of immunity, proper precautions go far to decrease the dangers; and if the wound is attended to in time by a skilled surgeon, the patient may make his mind comparatively easy.

Recognizing Symptoms of Hydrophobia

Rabies in the dog commences with the ordinary sings of ill health. The poor creature is dull and unhappy, its eye is dim, its nose is hot and hard, and its manner is listless and dejected. Indeed, a sick dog is in many ways like a sick child. It betrays symptoms of malaise, is downcast, and anxious to be caressed and comforted. Here, however, is one of the most fertile sources of danger; for from the moment that a dog begins to sicken from hydrophobia, its saliva is infectious, and there is consequently nothing more dangerous than ever to allow a dog to lick the hands or face. The deadly virus may be absorbed in the very slightest abrasion of the skin.

The first stage is soon over, and to it succeeds the second, in which the distinctive symptoms begin to show themselves. As to the cause from which rabies spring, nothing yet developed enables us to satisfactorily account, it having been, in fact impossible to trace the origin of the germ; all we know certainly is, that it is a disease of the nervous system, coupled with a morbid condition of the salivary glands, the saliva itself, the fauces or throat, and the adjacent parts. Hence it follows that, as soon as the premonitory symptoms of general sickness and discomfort are over, the more definite characteristics of the disease itself are almost unmistakable. The poor animal suffers from an irritation of the gums and tooth that makes him – something like a teething child – bite and gnaw at everything that comes in his way. He will gnaw at his chain, and at the woodwork of his kennel, or at the mat on which he lies. He will take up in his mouth and chomp stones, straw and pieces of dirt or filth. His teeth apparently pain him, and he will ruo and scratch at them with his forepaws, as if a fish bone had stuck in the gum and he were trying to get it out. But most significant of all is the change in his voice, due to incipient inflammation of the throat and larynx. The bark of a dog in health is clear and sonorous; it barks with ease, as it were, each yelp yielding a distinct and clear note. A rabid dog, on the contrary, utters a bark which, once heard, can never be mistaken, a sort of strangled, stifled howl, lugubrious in its tone, and uttered with an evident effort. It is not, indeed, too much to say that a skilled veterinary surgeon can detect a mad dog by its bark alone; and that the moment a dog’s bark is altered in its timbre, it should be carefully watched to see if other symptoms are not present.

Nor is this all. Beside the inflammation of the throat, there is also cerebral disturbances, which lead to a set of symptoms of its own, equally important and significant. The rabid dog is uneasy and anxious. He roams from place to place, seeking rest and finding none. He starts up suddenly and snaps at the air, as if he were vexed by phantoms. He watches intently imaginary objects, following them closely with his eyes, as if meditating a spring. Above all, he conceives a violent dislike to his own species, the mere sight of another dog driving him at once into an uncontrollably fit of passion. Hitherto he will have been sufficiently docile and tractable, obedient to his master’s voice, anxious for the customary caress, and, if anyting, more than usually demonstrative of his affection. But toward the end his restlessness increases, and he seizes the first chance of straying away from home. Wandering into the street, he runs recklessly and listlessly up and down, his tail between his legs, his hair foul and bristling, his whole look haggard and woe begone. The evil fancies which haunt him grow on him. Soon he becomes furious, attacking other dogs, horses, cattle, men – everything in short, that comes across his path. In this, the last state, the disease is only too apparent; further doubt as to its nature is impossible. As a rule the dog is killed, although often not before he has spread the disease over a whole district. If not killed, he soon dies in the nature course. His rage increases, but he becomes weaker and weaker. His legs fail him, paralysis sets in, and he expires in convulsions.

Such, then, is the course of the disease in the dog. With regard to it we ought especially to notice two things: First, that dread of water is rarely, if ever, present. A rabid dog will, on the contrary, lap water eagerly; it relieves the suffering caused by his swollen throat. Second, that until the very last stage of the malady, and often even in that, the dog remains all his affection for and obedience to his master – nay more, seems to be aware of his miserable condition, and to crave for help and sympathy. Indeed, in this respect a sick dog is, as has already been said, strangely like a sick child. The lesson to be drawn from this is very obvious. The moment a dog appears at all ill he should be suspected, more especially if he should have been bitten by a strange dog, or have the scar of a bite upon him. It is as easy to tell when a dog is ill as to tell when a child is ill. A dog in health is bright and animated, runs freely about, and carries its tail erect; its nose is moist, its tongue clean, its coat clear and “satiny,” and its eye full of light and life. A dog that is out of health is the very opposite of all this; and the dog that is out of health when hydrophobia is prevalent should be at once secluded. In a few days either he will be well again, or else the distinctive features of the disease will have shown themselves, and further doubt will be out of the question. What then is really essential is that hose who keep a dog should watch him most carefully, to see that he is bitten by no other dog. But they sho8ld also watch his health, and note any alteration in his habits, however slight.

Bitten by a Rabid Dog

Then run the risk of a greater still.

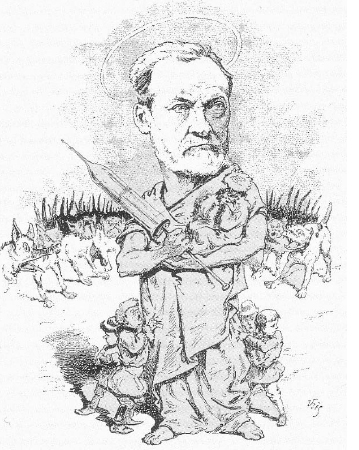

Louis Pasteur’s Cure for Hydrophobia

A word here about M. Pasteur, the distinguished chemist. Only the other day he communicated the results of his four years labor to the Academie des Sciences, and the facts established by his experiments are in substance as follows:

“If the virus of rabies be transmitted from the dog to the monkey, and then from the monkey to monkey, it will be found that after each transmission the virulence of the virus becomes enfeebled. If the virus thus enfeebled be transmitted to a dog or animal of that species, it will still remain attenuated. By a few transmissions of the virus from monkey to monkey there can easily be obtained a virus so attenuated that it shall never communicate, by hypodermic inoculation, the disease to a dog. Inoculations by trepanning of such virus will likewise produce no result; but, notwithstanding, an animal will not be rendered thereby proof against the disease. The virulence of the virus becomes, on the contrary, augmented in his passage from rabbit to rabbit. If a dog be inoculated with virus thus augmented in power, a far more intense form of the disease will be manifested than that apparent in ordinary canine madness, and it will invariably prove fatal.”

By applying these and other observations, M. Pasteur obtained views of different degrees of virulence, and succeeded, by inoculation, of the milder qualities, in preserving animals from the effects of more active and moral kinds. For example, after several days longer than the shortest incubation term, M. Pasteur extracted virus from the head of the rabbit which had died of the disease, and inoculated successively two other rabbits. Each time a dog was inoculated with the virus, which, as has bene seen, would increase each time in virulence – the result was that the dog was ultimately rendered capable of bearing a virus of mortal strength, and became absolutely proof against canine virus. M. Pasteur, however, anticipates that the time is still distant when canine madness will be extinguished by vaccination, but, pending that consummation, he feels pretty certain that he will be able to avert the consequences of a bite from a mad dog. He says: “Thanks to the duration of incubation after a bite, I have every reason to believe that patients can be rendered insusceptible before the mortal malady has had time to declare itself.” M. Pasteur stated in conclusion that he had solicited the Minister of Education to appoint a commission to test his experiments.

Meantime it is better, as I have said, to assume that no cure is known. The bread facts of the case are simply these: Of those who are bitten by mad dogs, comparatively few take or contract the disese. Of those who are bitten and escape it willb e found that the majority have treated the wound vigorously – or, as the doctors say, heroicly – cutting it out, or cauterizing it severely. But of those who contract the disease, all die. No single case of recovery is upon record. I do not like to use hard names, but I know what I think of those who pretend to have a specific for hydrophobia and are who are willing to sell it. Trust in no quackeremedy; the danger is too terrible to be trifled with. Go to the surgeon at once, if you can. If a surgeon is not within immediate reach, then use knife, gunpowder, lunar caustic – anything that will burn out or cut out the wound, and that you have the courage to bear.

Dangerous but Rare

Of police measures intended to prevent or stamp out the disease, I have not spoken. I have rather written for those who may be, reasonably enough, anxious to know how to protect themselves against this disease, and what errors to avoid. D.C.M.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing