Originally published in the “English mechanic and world of science, Volume XXIII” in 1876.

We cannot follow the author in the details of questions of pure science and their industrial applications, which he-treats by turn with the same competence: we can only summarily expose the doctrines which he has tried to make prevailing, and the applications which he has drawn from them with respect to beer making.

The History of Beer

Known in the earliest antiquity beer is an infusion of hops and germinating barley, which is made to ferment, and which rest and decanting afterwards bring to almost perfect limpidity: it is in reality barley wine. Theophrastus, in the second century B.C., already gives it that name, which is quite right. However, there is, between the two beverages, a considerable difference. Grape wine rarely fails, and, once made, keeps generally well. Barley wine, on the contrary, is nice and difficult to make: the best brewer often fails and sees himself forced to throw away the entire produce of an operation. Moreover, beer keeps with difficulty—it is soon altered.

There is another difference. Grape juice is left to ferment by itself, whilst it is quite another thing with beer. With cooled barley malt there is put some barm, collected from a previous fermentation. So that all the beer drunk since the origin of this beverage was born of itself from one operation to another. That which is poured in beer-houses goes back through a real genealogical line to that which wan made, for the first time, by some Eastern tribe. Barm is one of man’s domestic conquests, like wheat and silk-worms, which are propagated by his hands, without any one knowing exactly when, where, or how man discovered these treasures.

Why has this practice of using barm been perpetuated from age to age in beer-making, while such a thing is not done with grape malt? Twenty years ago it would have been difficult to answer this question. It is easy to answer after the studies of which fermentation has been the subject of late years, and those of M. Pasteur in particular.

Fermentation

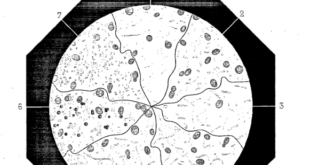

A ferment—we only speak of ferments which relate to the history of wine or beer—is a microscopical plant, a kind of mushroom, only differing from those we know by its very small dimensions. Thi3 mushroom consumes oxygen in order to live and produce carbonic acid; then it is only developed in fixed conditions of moisture and heat. Up to this nothing distinguishes it from any other mushroom. But there is this: If you introduce barm in malt, this barm carries with it a small quantity of air—that is, of oxygen. Finding conditions favourable to its existence, it germinates and multiplies, consuming at first this little quantity of oxygen; then—and this is the peculiarity of all ferments—when all the oxygen which was within its reach has disappeared, it takes some from surrounding bodies, decomposing them if necessary. Malt contains a special sugar formed by a great proportion of oxygen combined with carbon and hydrogen. Barm, in order to live, decomposes this sugar, taking a part of its oxygen; sugar thus altered becomes alcohol. All fermentation has no other result. Carbonic acid which foams over vats is the result of the life of the ferment.

If there were only one mushroom ferment able to live thus in malts by decomposing sugar to make alcohol, fermentations would always follow the same regular march; beer and wine could be made with the same ease. It is not so however, and M. Pasteur explains thus the difference:—

One must think of malt as a kind of field ready for culture. In beer-making, this field is sown with the barm which is added. The latter germinates, multiplies to infinity, and gives a crop which is no other than the same barm increased a thousand times, which is found after each operation. But on this liquid ground represented by the malt, vegetation is submitted to the same laws as in the fields. Twenty plants contend for place and struggle for life. All that is sown does not grow. Tare sometimes takes the place destined to corn. The seed which has for itself number and strength annihilates the other seeds. The plant which grows best in the ground and has spread first stifles off the others as they appear. It may happen that the designedly-sown seed undergoes, through some cause, a delay in its development. The other seeds have then time to shoot; they take up the place left free, monopolise the place and the substance of the soil; it is a ruined crop.

All that is very well known by agriculturists; things do not happen differently, according to M. Pasteur, in wine and beer making. Let us first take the case of wine malt. It is ready-sown; the mushroom which will ferment it exists, according to M. Pasteur, in abundance on the peel of the grapes themselves. As soon as these are crushed, the ferment, being then in favourable ground, germinates and multiplies; it does so alone, because grape molt is acid, because it contains bitartrate of potash, and for other reasons perhaps. So much so that grape malt constitutes a ground favourable to the development of barm, to the almost absolute exclusion of any other mushroom of the same kind. Accordingly, the other seeds which are mingled with those of barm, are abortive, because circumstances are not favourable for them. Let us suppose a light soil, in which has been sown seeds preferring that kind of ground, and others which only grow well in a heavy soil. The first will soon shoot, whilst the others will remain poor and even perish, because all the space and the substance of the soil are already taken up by the plants which have grown quickest. It is tor a similar reason that the fermentation of wine is always spontaneous and regular—spontaneous, because the barm necessary to change sugar into alcohol exists originally in the malt itself; regular, because the vegetation of the mushroom exclusively favoured by the nature of the malt, prevents that of the others, which are no doubt mingled with them.

Beer Fermentation is Different than Wine

It is otherwise with barley malt. Germs of the mushroom which changes sugar into alcohol are also always there, but they are not there alone, and above all they are not, as in the grape malt, in conditions exclusively favourable to their development. If barley malt is given up to the spontaneous action of all these germs, the right ones may develop and produce beer (it is thus that the first beer has no doubt been made); but it may happen as well that the wrong ones have the start and monopolise the common ground, producing other decompositions than that of sugar into alcohol. The result will be acid, putrid, viscous, bitter—in short, undrinkable beer. M. Pasteur calls all these ferments disease ferments. He finds them again, with their characteristic features, in the deposits from bad beer. All the art of the brewer consists in preventing the development of these hurtful plants, which the vine-grower does not mind, because they do not grow well in grape malt.

The practice of using barm, or of sowing the right mushroom in barley malt, has no other motive than to monopolise, so to say, the ground for the profit of the useful plant: its culture is helped in order that it may hinder the development of disease ferments. The use of the barm is not, however, sufficient to prevent all misfortune, and, more than once, especially with the old method of beer-making, either during the operation itself or soon after, the germs of disease used to grow and made their work. Moreover, it was necessary to make beer only in proportion to the consumption, for it could not keep.

Low Temperature Brewing

A first progress has been made by substituting low fermentation for high fermentation, formerly alone used. In the process of low fermentation, beer is made at a low temperature (this is not, however, the origin of the names low and high fermentation); then it may be kept a rather longer time: it is made in winter for summer consumption, on condition, however, to be kept cold. This, evidently, is a cause of great expense. This beer must be carried in ice-lined waggons, and kept in ice safes up to the moment of serving it up. It is estimated that no less than 100 kilogrammes (more than lewt.) in the average are required for one hectolitre (22 gallons) of good beer from the moment it is made to the time at which it is sold. The Dreher firm, of Vienna, alone consumes 45,000,000 kilogrammes (more than 40,000 tons) of ice a year!

The reason for the use is still the same: cold stops or, at least, delays the development of disease ferments, whilst it allows that of the barm. The others are not annihilated, but only sleep, and would awaken if the temperature should become ever so little softer around them.

By the process of high fermentation the price of beer is raised in proportion to the numerous unsuccessful operations. By the process of low fermentation the price remains high on account of the quantity of ice required. M. Pasteur, following up the course of his ideas on fermentation, put to himself the question whether it would not be possible to make a beer free from all disease ferment, which would consequently be a good keeping beer, not requiring to be always in contact with ice. M. Pasteur tells us, in the very preface of his book, that the idea of this research was inspired to him by our reverses; he has undertaken it soon after the war, and has pursued it without ceasing, “with the resolution to take it far enough to mark, with a durable progress, an industry in which Germany is superior to us.”

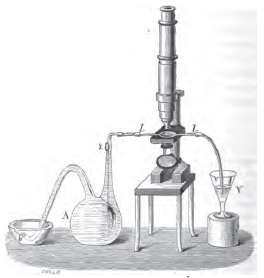

It is indeed very clear that, if a beer can be made in which there is no disease ferment it will be possible to keep it indefinitely, lit wine, at the ordinary temperature of wine and beer vaults. Such has been the aim of M. Pasteur. To gain this end he has first tried to get pure barm, not in malts, but in sugar solutions, and in solutions of other salts favourable to the germinating of barm. In cultures of this kind the barm collected at first is not yet pure enough: it is mingled with disease ferments; but the latter do not develop theo. selves (conditions not being favourable for them), whilst barm multiplies to infinity; they become more and more rare, and finally disappear. After a certain number of successful cultures, practised in this way, the barm thus obtained is sensibly pure. It is kept in dose vessels, and it is the one which will be used.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing