Originally published in Auburn Seminary Record, Volume 12, March 10, 1916, No.1

The Organizing , Training and Inspiring of Church Officers

Address by Rev. William R. Taylor, D.D., Before the Alumni Conference, May 9, 1916

III. The Inspiring of Church Officers

And now abideth organizing, training and inspiring, these three; but the greatest of these is inspiring. For if a man be truly inspired, he will do something, and that something will be the biggest and best thing he is able to do. He will probably make mistakes, but unless he be a hopeless crank in which case he must be suppressed, he will make something besides which will be worth while.

The two great means for inspiring of men are the same as Phillips Brooks named as the two elements in preaching – Truth and Personality.

Truth in all its forms–abstract proposition, noble ideal, concrete fact–has a strange power to inspire men; and never more than today. In the Bible, in history, in contemporaneous life what inexhaustible sources of inspiring truth await employment! To dig it out, to appraise its value for the purpose in mind, to adapt it for use must ever be one of the chief tasks of the minister who would inspire his Church officers.

The requisities of Personality for the inspiring of men are first of all, possession by an ideal. Not possession of an ideal, but possession by an ideal. Phillips Brooks quotes with approval the remark of some man to the effect that every preacher must be possessed by the “demon” of preaching. Every man who would be an inspiring leader must be possessed by teh Demon of something or other. In the case of the Christian minister we are in no doubt what particular demon-ideal should possess him.

Margaret Fuller may say “I don’t know where I’m going; follow me.” Abraham “went out, not knowing whither he went.” So must every one do, to a greater or less extent, who walks by faith. But there must be some ideal, some goal, to point to if we expect him to follow us.

And then come at least five personal qualities which must be exhibited in the pursuit of the ideal.

First, Power. No man can be stronger than God made him to be. But few men are as strong as that. “Is he a strong weak man or a weak strong man?” was the question once asked of me concerning a friend. The strong weak man is the man who makes every atom of his small strength count. The weak strong man is the man who lets some of his great strength go to wste. Some are stronger than others; but the weak man can usually develop strength enough for his task–his task–if he wills it.

This leads to the second requisite, Courage–the courage that is born of faith. No coward, no timid man, no man afraid of new and larger undertakings, no man unwilling to take at least a reasonable hazard can every hope to be an inspiring leader.

Third, Enthusiasm–the enthusiasm born of hopefulness. “I am come to case fire on the earth,” said Jesus. Until we catch some of that fire ourselves we can hardly expect to communicate to others.

Fourth, Reality–genuiness, sincerity, the real thing. Some shams and hypocrites and self-seekers manage to become leaders of great inspirational power. But it is only a question of time when their real character is discovered and their influence vanishes. The inspiration of the real man is self-reproducing ad infinitum.

Fifth, Unselfish Devotion int he pursuit of the ideal. There’s nothing that counts more than this. It is the power of the Cross. “I, if I be lifted up, will draw all men unto me.”

The English author of Elie Metchnikoff’s work on “The Nature of Man” (Metchnikoff was one of those who left all to follow Pasteur) refers, in his introduction to an article which appeared in a Paris newspaper describing the life of a group of young scientists whom Louis Pasteur gathered around him at the Pasteur Institute. “A little body of men, forsaking the world and the things of the world had gathered together under the compulsion of a great idea. They had given up the rivalries and personal interests of ordinary men, and, sharing their goods and their work they lived in austere devotion to science, finding no sacrifice of health or money or what men call pleasure too great for the common object. Rumors of war and peace, echos of the turmoil of politics and religion, passed unheeded over their monastic seclusion; but if there came news of a strange disease in China or Peru a scientific emissary was ready with his microscope and his tubes to serve as a missionary of the new knowledge and the new hope that Pasteur had brought to suffering humanity. The adventurous exploits and the patient vigils of this new order have brough about a revolution in our knowledge of disease and there seems no limit to the triumphs that will come from the parent Institute in Paris and from its many daughters in other cities.”

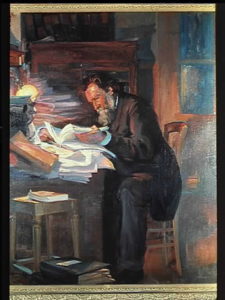

The power of Louis Pasteur to organize, train and inspire men is no mystery to those who knew him or have read his life. It was the power of Truth plus Personality. True, he was a man of transcendent intellectual gifts for his chosen field. But these gifts alone would never had made him the inspirer of that band of devoted followers and fellow-workers. It was the high-minded, high-hearted, high-souled quality of the man,–the power, the courage, the hopeful enthusiasm, the reality, the unselfish devotion with which he served the ideal which possessed him.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing