In the beginning we eagerly greeted the arrival of these wines, but we soon made the sad experience that this trade caused great losses and endless troubles because of the disease to which they are subject.*

It was for this reason that Ildephonse Favé, aid-de-camp to Napoleon III suggested that the Emperor commission Louis Pasteur to study the wine diseases. A formal request was sent by Favé, to which Pasteur quickly accepted. Pasteur had become acquianted with the problems of conserving wine earlier during his work on fermentations. Pasteur quickly set out on the work. After inspecting various different wine-producing localities, Pasteur came to the alarming conclusion that, “there may not be a single winery in France, whether rich or poor, where some portions of the wine have not suffered greater or lesser alteration.”

French Wine Disease Results Discussed with Napoleon III

Nearly two years later, Pasteur was invited to the château Compiègne, the royal residence of the Emperor, to formally present his findings on the French wine disease problem. Along with the other guests, Pasteur was introduced to the Emperor, to which he declared, “Ah! I have long wished to congratulate you on your fine work.”

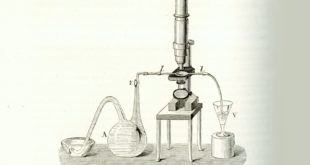

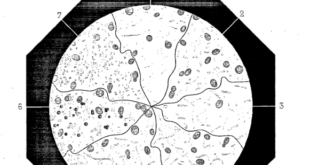

After the usual pomp and parading of wealth by the royal family, which included dramatic plays, seven course meals and wild hunts, Pasteur’s presentation was scheduled. For nearly an hour Pasteur privately presented and discussed his report and drawings on wine diseases with the Emperor and Empress. He also provided specimens to be viewed under the microscope he brought with him. The demonstration then moved into the Empress’ tea-room where other guests received a demonstration. People were mesmerized by their first encouter of the microscope. Pasteur proposed a fun observation to compare frog’s blood and human blood. Before any of the men in the room could volunteer themselves, the Empress had already cut herself offering Pasteur her blood for the microscope. And, of course, everyone wanted to examine the blood of the Empress!

Pasteur Reflects on his Accomplishments

To end the affairs, the Emperor lead a dance in the grand ballroom to the tune of two full orchestras. Pasteur did not participate in the revelry. Instead he sat with the Empress and Lord Dudley, the inventor of the telegraphic cable designed to pass under the English Channel, to converse. Thinking of his experience at Compiègn, Pasteur wrote to his son Jean-Baptiste:

The honor of spending a week in the Emperor’s company which I have just received will make you understand the rewards of hard work and good conduct. You should therefore also work hard, so that one day, God willing, you may have the same satisfaction.*

The hard work Pasteur was referring to was his identification of the source of the wine disease and its nullification. For centuries wine makers had used makeshift methods, such as freezing and heating, to mitigate wine impurification. But what they lacked was the understanding of yeast, air and germs. Pasteur’s studies lead to the publication of Études sur le vin (On the studies of wine), a comprehensive investigation of the inner workings of wine fermentation. His methods of applied heat and minimizing exposure to bacteria in the atmosphere lead to a simple discovery, but one that would revolutionize the wine industry forever: industrial pasteurization.

* Debré, Patrice. Louis Pasteur. 1998. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing