It was the good fortune of the writer four years ago, to be the only guest — apart, of course, from “the guest of the evening”; — present at the dinner given to the venerable M. Chevreul by his colleagues of the Societé d’ Agriculture. The dinner was given at the Café Riche, and the chair was taken by M. Dumas, the great chemist; among those who had assembled to do honor to the senior member of this Agricultural Academy being M. Louis Pasteur. Unlike most public dinners, this, one, limited as it was to members of a society so small that all are more or less intimate with another, was not in any way a stiff and formal affair, and everybody was on friendly terms with his two neighbours long before the cognac of 1786 — year of M. Chevreul’s birth — was handed round as the crown and consummation of a dinner wholly and solely French. Nothing was put upon the table, whether solid or liquid, but had been grown upon French soil, and any stranger who had been privileged to sit at the board would have come away with the impression that the capabilities of the soil are infinite. It was in this illustrious company that the present writer first had the honor of meeting M. Pasteur, who, though not then so famous abroad as his more recent discoveries made him, was already regarded as the foremost man of science in his own country. It was easy to see that, even upon a festive occasion of this kind, M. Pasteur was unable to divert his thoughts from the mighty problems which he has for the last few years been steadily pursuing towards a solution, and genial as was his manner towards a stranger, the phrase alta mente revolvene seemed as if coined by the Latin poet to describe the pondering expression which now and again came over M. Pasteur’s face.

That expression, intensified in its earnestness by the solemnity of the occasion, must have been noticed by many of those who have seen him in his laboratory of the Ecole Normale, where is being carried on the noble battle against one of the most dreadful — perhaps the most dreadful — scourge which afflicts humanity. Wonderful as have been the discoveries which M. Pasteur has already made and brought within the reach of daily practice, these all, affecting as they did the animal and vegetable world alone, sink into insignificance beside the experiments which, if there is no check to the success that has attended them for the last few months, will render human beings, as well as animals, proof against hydrophobia as completely and as easily as the former can be made proof against small-pox vaccination. These experiments, it is no exaggeration to say, are being followed with as deep interest in the New World as they are in the Old, for M. Pasteur has already treated several patients from the United States and South America; and he is perhaps seen at his best when coaxing little children and persuading them that the process of inoculation which they are about to undergo “won’t hurt.” On the occasion of the writer’s last two visits to the laboratory at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, in the Rue d’ Ulm, four boys from Newark, in the State of New York, were among the crowd of patients waiting to receive the injection of the attenuated virus, which M. Pasteur believes will neutralize the more potent poison introduced into the system by the bite of a mad dog. These boys, the eldest only 14, had already been inoculated eight times, and they dreaded the operation so little that they were playing antics in the outer room, and making the most solemn and how solemn they can be when, to use their expressive phrase, they have to faire autechumbre — of the French smile by putting upon each other’s heads, the tall hat of one M. Pasteur’s assistants. Only one of these boys had been accompanied across the ocean by his mother, the three others being under the care of an American physician, to whom had been entrusted the handsome sum subscribed by the inhabitants of Newark. They are more expeditious in the United States than in Russia, or even in France itself: for these boys were bitten on the 2nd of December last, and within a week the money was subscribed, and they were on their way to Le Havre. By the end of the month the series of inoculations was completed, and on New Year’s Day they left for Le Havre upon their return voyage. In contradistinction to this, eleven Russians were bitten by a mad wolf in the neighbourhood of Lublin, and M. Pasteur, finding that they could not afford the expenses of a visit to Paris, offered to defray the whole cost himself. But when these eleven unfortunates reached the Russian frontier, they were detained there a month for the legalisation of their passports, during which period one of them died of hydrophobia, and now, as M. Pasteur says, there is little use of inoculating the others. For the basis of his theory is that inoculation must be effected within a month of the bite, that being a reasonable period to allow for the incubation of the disease; and though he does not refuse to inoculate persons who have been bitten at a more remote interval, the fact of their afterwards falling victims to hydrophobia would not in any way invalidate his theory. Inoculation can no more be a remedy against hydrophobia, when once it has declared itself, than vaccination can be against small-pox when once a patient is down with it.

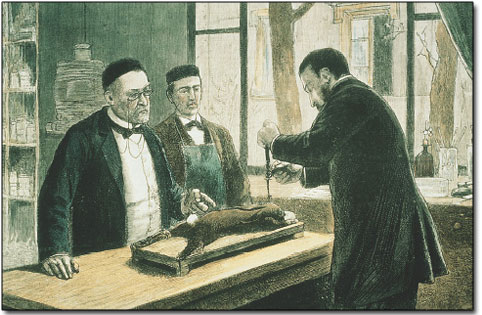

The inoculations are performed in the room which has hitherto been used as a study by M. Pasteur, while attending the experiments conducted in the laboratory. This laboratory, which is a building of one story in the gardens of the Ecole Normale, is very conveniently situated for M. Pasteur, who occupies a modest apartment on the second floor of the main building, and with a not very cheerful outlook upon the stables of the General Omnibus Company. Beyond the many testimonials and presents which M. Pasteur has received, and which are scattered here and there in pleasing confusion, there is nothing to arrest the attention in these rooms, placed at his disposal by the State: and M. Pasteur is more often at home in the laboratory, especially since his recent discoveries about hydrophobia have been brought into the domain of practical science. The boulevard journals are wont to indulge in ponderous and antiquated jokes about the perils of a journey from the heart of Paris — that is to say, from Tortoni’s or Hignon’s — to the Odéon Theatre; but the Odéon is not much more than a half-way house to the Rue d’ Ulm, and it may be regarded as proof of the respect which M. Pasteur’s experiments command, even from these frivolous persons, that they do not indulge in pleasantries about changing horses at the Odéon and breakfasting at Foyot’s while the change is being made. They have got so much to say about Mr. Pasteur’s laboratory that they spare their readers all this clumsly trifling, and it is much to their credit that they do not attempt ot make capital out of the experiments tried upon the rabbits and guinea-pigs which people the basement of the building. The experiments upon the rabbits certainly seem rather alarming to a novice, but yet it may be questioned whether the animals suffer much in the initial stage; for after they have been tied down by the four legs to a flat board, they are put under chloroform, and it is not until they have become quite unconscious that the operation of trepanning is performed. The rabbit does not recover consciousness until the top of the head has been sewn up again, and the suffering does not commence until hydrophobia declares itself. It is the same with the dogs, which, it may be observed, are not kept at the laboratory in the Rue d’Ulm, but in a building in the Rue Vanquelin hard by, where they may be seen in every stage of hydrophobia, some in a dazed and somnolent state, others foaming at the mouth and dashing themselves furiously against the bars of their iron cages.

The enemies of vivisection may say that all this is very cruel, and that the end does not justify the means. Let M. Pasteur answer them in his own words. A short time ago he was conducting some experiments with reference to the oxygen at the air, and in the course of these he placed a sparrow beneath a glass bell. The bird, after having consumed the quantity of fresh air beneath the glass, began to gasp for breath, and eventually became unconscious. M. Pasteur then placed a second bird beneath the bell, and the latter, passed suddenly into a vacuum, at once dropped dead. One or two of those present hazarded the remark that this was cruel; whereupon M. Pasteur, as the first sparrow came to again, said,

“I shall never have the courage to kill a bird for amusement or sport, but when experiments have to be made, I do not know the meaning of the word ‘scruples.’ Science has the right to invoke the sovereign character of the end aimed at.”

It must be said, also, to M. Pasteur’s credit, that he is quite willing to risk his own life in the cause of the science of which he is the passionate and devoted servant, and he gave a very striking proof of this when he wanted to get some rabie virus from a large bull dog which had gone mad, and which had refused to bite a rabbit put into the cage where he was confined. “We must have some of his saliva to inoculate the rabbits with,” said M. Pasteur, and he ordered his attendants to secure the dog with a lasso, and this being done, he was dragged on to a table, and tied tightly round the jaw and held fast while M. Pasteur, with his face almost touching the brute’s muzzle, sucked up through an elongated tube a few drops of saliva.

The story of M. Pasteur’s life is, apart from his scientific labours, a very brief and very simple one. He was born at Dole upon the 27th of December, 1822; his father, who had served as a soldier under Napoleon, following the profession of a tanner. When Louis Pasteur was only 2 years old, his parents moved to the town of Arbois, where his father had purchased a tannery. The boy was sent to the local school, and afterwards to Besancon College, preparatory to entering the Ecole Normale at Paris. It was while as Besancon that he first exhibited a liking for chemistry, and in this, too, he became so rapidly proficient that the professor who taught that subject was soon reduced to admit that Pasteur knew more than he did. He then went on to Paris, but coming only fourteenth of the candidates for the Ecole Normale, he determined to prepare for it during another twelvemonth rather than enter so low down on the list. A twelvemonth later, he passed fourth out of a hundred candidates, and so he joined the Ecole Normale, where, as also at the Sorbonne, he devoted himself with passion to the study of chemistry. M. Dumas, whom he was destined to succeed forty years later at the Academie Francaise, was then Professor of Chemistry at the Sorbonne, and Louis Pasteur gradually perfected himself in the knowledge which has since been exercised for the benefit of the whole human race. This is not the place to narrate in detail the various discoveries which, beginning with his experiments in molecular physics, led up by gradual steps to what bids fair to be the crowining glory of his illustrious career. So deep was his devotion to his studies that upon the morning of his marriage to Mdlle. Marie Laurent, daughter of the Rector of Strasburg University, where he had been appointed assistant professor of chemistry, he had to be fetched from his laboratory a fact which Madame Pasteur recalls with an indulgent smile telling eloquently of the happiness which has attended their married life. The only breaks in that happiness have been the paralytic attack which he was seized with in 1868, just after his great discovery of the cure for the silkworm epidemic, and which has left a trace of lameness behind it, and the war of 1870, which was much felt by M. Pasteur, whose son did his duty nobly.

The remedies against chicken-cholera, red fever in pigs, splenic fever and rot in cattle and sheep, are each of them sufficient for the fame of one man, yet all of these and the many other discoveries which preceded them sink into insignificance beside the prevention of hydrophobia. The experiments which have led to to his discovery were being turned over in M. Pasteur’s busy brain when he attended the International Medical Congress in London four or five years ago, and they were already far advanced when he came to receive a complimentary degree at the jubilee of Edinburgh University last April twelvemonth. These and all honors showered upon him M. Pasteur accepts without any false modesty, but with evident indifference, except in so far as the proffer of them shows that the value of his discoveries is universally recognised. M. Pasteur had his enemies, of course, the faddists who object to vaccination and vivisection attacking him not less bitterly than Rochefort, who will not believe in his scientific knowledge because he is a good Catholic; but the kindly old gentleman of middle height, and with full-bearded face crowned by a skull cap, can afford to let the sceptical aim their malevolent shafts at him, secure in the knowledge that his life has been spent in doing good. — World.

Download Original “Pasteur on the Rue d’Ulm” Article

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing