This article is an excerpt of Gibson’s larger work, “The Wonders of Scientific Discovery.”

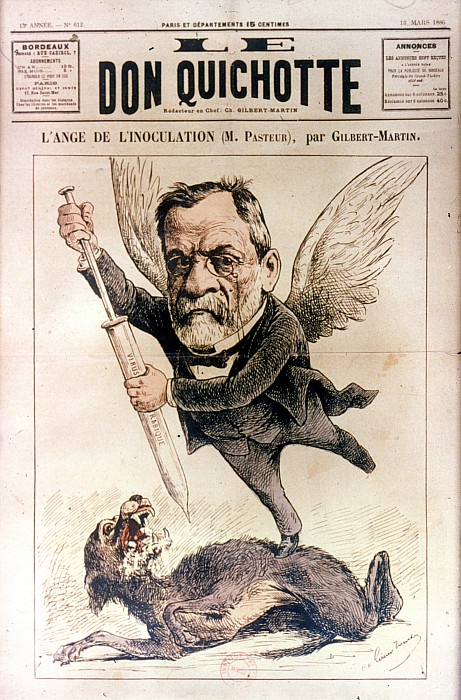

It has been remarked in the preceding chapter that in the mind of the general public it is in connection with hydrophobia that the name of Pasteur is best known. The year before Pasteur’s discovery there were sixty-seven deaths from hydrophobia in Great Britain alone. In France there were no less than three hundred deaths in one year, while the death-rate in Prussia and Austria was even more serious.

When a person was bitten by a mad dog, or more correctly a dog suffering from rabies, there was grave danger of hydrophobia setting in. The trouble did not appear immediately; the wound healed, and in about a month or sometimes longer there appeared very distressing symptoms. Not every person bitten by a mad dog died, but if hydrophobia did set in there was practically no chance of recovery. The writer of the article on Hydrophobia in Chambers’s Encyclopedia (1876) says: “Little need be said of the treatment of hydrophobia, for there is no well-authenticated case of recovery on record.”

The malady showed itself in a feeling of unrest, and the patient’s face became terror-stricken, giving suspicious side-long glances as though constantly looking for hidden dangers. Then followed a great difficulty in swallowing, especially any fluid; even the sight or sound of water brought on paroxysms. The spasms were not unlike those accompanying lock-jaw (tetanus); the patient became delirious and ultimately died of suffocation.

Pasteur’s discovery was that by inoculating a person with matter taken from the spinal cord of an animal which had died as a result of modified hydrophobia, he could bring about protection against the fearful malady. It was not a cure, indeed hydrophobia is still incurable, but it was a protection. A very weakened injection is given at first, then a stronger one, and so on over a period of some days. Fortunately it is not necessary for every person to be inoculated against the small chance of being bitten by a mad dog. It is time enough to think of the treatment after one has been bitten, for the disease is slow in developing, taking at least a month to appear. Before this time of incubation has elapsed the treatment brings about a condition of things that protects the patient against the germs.

Of course Pasteur did not commence with experiments upon human beings. It meant the death of many dogs and rabbits before he gained sufficient knowledge of the different injections. Surely the results which followed justified the death of these dumb creatures! It is well to emphasise one point which the anti-vivisectionists omit to mention that none of these operations are carried on except with the aid of an anaesthetic. For a single injection it was sufficient to give a local anaesthetic. One of our professors who visited the Pasteur Institute says that the animal “does not suffer even discomfort, and I have seen a rabbit going on eating while the operation was being performed.” When it was necessary to carry out any surgical operation the animal was chloroformed in the usual way.

After Pasteur had satisfied himself that he could protect animals against the occurrence of hydrophobia, his next step was to try the treatment upon a human being. The first case was that of a little fellow of nine years of age, who had been very severely bitten by a rabid dog. There were no less than fourteen different wounds upon the boy, and when Pasteur consulted two of the most eminent physicians, they said that they were perfectly willing to accept responsibility for the experiment, as it was certain that the boy would develop hydrophobia, and there was, of course, no possible chance of recovery. Pasteur commenced his treatment of inoculation, and when the time of incubation expired, there were no signs of hydrophobia, and the boy made an excellent recovery.

One eminent British physician who visited the Pasteur Institute has given us the following description: “He [the assistant] handed the syringe to the operating doctor, who, taking a fold of the skin (which had been previously washed and purified with carbolic acid), inserted the point of the needle, injected about half a syringeful, withdrew the needle, and the patient passed on. The syringe was handed back to the assistant, who carefully sterilized it. The whole operation seemed to take only a few seconds. A continual stream kept passing from one room to another, each patient, as he went through, undergoing the same process of inoculation. Everything was done in the most orderly fashion, and one could not but feel that Pasteur, who was standing in the room whilst this was going on, had every right to feel proud.”

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing