By DR. HERMANN M. BIGGS.

The prophylactic treatment of rabies was one of the most significant and important discoveries in the whole history of medicine, and most notable contribution to preventative medicine by Pasteur whose centenary has just been observed. Its importance does not lie so much in the actual number of lives saved, as the deaths from rabies never have been considerable in number compared with most of the other more common diseases, but lies rather in the scientific significance of the discovery and the hopeless and dreadful nature of the disease itself. With this contribution was recorded fro only the second time in the history of medicine a method for the specific prevention of an infectious disease affecting human beings the first being the discovery of vaccination for the prevention of smallpox. The discoveries of the methods for the prevention of typhoid fever, diphtheria, yellow fever and cholera all came at a much later date.

For some time previous to the application of the preventive treatment for rabies to a human being, Pasteur had been conducting extensive researches for the causation and prevention of rabies in animals.

It was not until complete protection in a long series of experiments had followed the application of the treatment to animals inoculated with doses of rabies virus or subjected to the severest infections through the bites of dogs suffering from ordinary street rabies that Pasteur ventured to subject a human being to the treatment.

The results of the earlier research were published from 1881 to 1884. Then after long experimentation and repeated success in the protection of animals, Pasteur determined to apply the treatment to the first favorable case which presented itself in a human being severely bitten by a rabid dog.

One feature of rabies in human beings and animals, which adds greatly to its terror, is the fact that once the disease has developed not only does it involve the greatest possible suffering (which is most fearful in itself both to the subject and to the observers) but it invariably proves fatal. On the other hand, under natural conditions, only a comparatively small percentage of all persons bitten by rabid dogs develops rabies. Pasteur had found that bites about the face and neck were especially fatal and that practically all untreated cases of this kind developed the disease.

On Oct. 26 following, Pasteur made a statement at the Academy of Science, describing the treatment of Meister. Three months and three days had passed, and the child had remained well. After the completion of Pasteur’s statement, which was received with great enthusiasm, Bouley, then Chairman of the Academy, said:

“We are entitled to say that the date of the present meeting will remain forever memorable in the history of medicine, and glorious for French science, for it is that of one of the greatest steps ever accomplished in the medical order of things, a progress realized by discovery of an efficacious means of preventive treatment for a disease, the incurable nature of which was a legacy handed down by one century to another. From this day humanity is armed with the means of fighting the fatal disease of hydrophobia, and of preventing its onset. It is to M. Pasteur that we owe this, and we could not feel too much admiration or too much gratitude for the efforts on his part which have led to such a magnificent result.”

As soon as Pasteur’s paper was published, the knowledge of his success was rapidly transmitted to every country, and people bitten by rabid dogs began to arrive at the laboratory from all parts of the world. The service for chief business of the laboratory. It was not long before four American cases went to Paris for treatment.

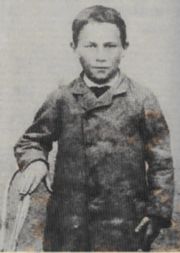

In November, 1885, four months after the treatment of the first treatment of the first case and only one month after the establishment of the service, four children of workmen in Newark were bitten by a rabid dog. The press gave the widest publicity to all the facts and details, and The New York Herald raised a fund to send these children to Paris. They were accompanied by Dr. Frank Billings, a Boston veterinarian of distinction, who had given the subject considerable attention, and had been a student with the writer at the Pathological Institute in Berlin during the previous year.

At that time I was in charge of the Carnegie Laboratory of the Bellevue Hospital Medical College. That was the first laboratory in this country specifically erected and devoted to teaching and investigation in bacteriology and pathology. Mr. Carnegie became greatly interested in the wide discussion of the subject of rabies, and wished a representative of the Carnegie Laboratory to visit Paris at once to study the method of treatment. I was commissioned to undertake that work. I went to Paris, and was at Pasteur’s laboratory — there was no Institute at that time — while the first American children were being treated, in December, 1885, and subsequently, and followed the workday by day. About forty patients were being treated daily, and they came from all parts of the world. This number rapidly increased. The laboratory at that time was a very modest one, and had only comparatively meager resources.

Numbers of distinguished medical men were already beginning to visit Paris to see Pasteur’s work, and I Particularly recall that among the group of Englishmen there at that time were numbered Sir Joseph Lister, afterward Lord Lister, who had made such valuable contributions to the study of surgical infections and to the development of antiseptic surgery; Sir Ernest Hart, for many years editor of the British Medical Journal; and Sir Victor Hershey, perhaps the most distinguished British neurologist and research worker in cerebral localization of that time.

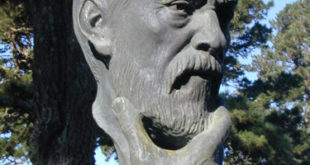

Each morning Pasteur visited the laboratory where the inoculations were being administered. He still showed plainly the effects of the paralytic stroke which had had in 1868, and from which his recovery was despaired of for a long period. He limped slightly and both the arm and face on the affected side showed limited motion. He was pale, always grave and taciturn, and spoke but little excepting to give directions or to formally greet visitors, and each day soon retired to his private laboratory.

Pasteur saw each one of the new patients who came to the laboratory for treatment and was very kind and gentle. There were many very poor people among these patients who were unable to meet living expenses in Paris, and for them Pasteur provided the means, often from his own resources. He always disliked to be disturbed when working in his private laboratory and access to him at such times was exceedingly difficult.

Immediately after the announcement of his discovery and the establishment of the service for the treatment of rabies, a movement to raise funds for the erection of a national institute began, and it rapidly swept over the whole of France. Contributions also came from many other countries, and the French Government made a large grant toward the establishment of the Institute Pasteur. A movement also was stated for the establishment of Pasteur Institutes in other countries. The men who took charge of these were trained and commissioned by Pasteur. An institute was established in New York under the direction of Dr. Gibier, and later arrangements were made for treatment at a laboratory in Philadelphia.

About 1901 the Department of Health of the City of New York made arrangements to give the treatment free. Since that time about 200 cases a year have been treated and the death rate in these cases averaged about one-half of one per cent. These results are almost identical with those which have been generally obtained in other laboratories where many cases are treated. There always has been much discussion as to the death rate from rabies previous to the introduction of this method of treatment, but it has been estimated at between 15 and 40 per cent.

The treatment for rabies was the last important research which Pasteur undertook. For several years subsequently he was engaged in overseeing the construction, and later the administration, of the new institute; then his health failed and a little later he died.

The specific cure of rabies is not yet known and in the forty years since the publication of Pasteur’s reports but little of importance has been added to our knowledge of the disease.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing