He asks but very few questions, indeed, sometimes none at all about how applicants for treatment came to be bitten.

About 10 a.m., Dr. Graucher, the chief assistant of Dr. Pasteur, walks across the graveled spot. He is a well known man in Paris. Already his exterior attracts attention. He is slender, bald, extremely pale, and has a Mephistophelean profile. He dresses in black, and his hands are encased in black gloves. Observing his self-possessed manner, one would suppose that he was a partner of Pasteur’s secret, but he is only his well-paid medical instrument. The exact way of manipulation for preventing rabies by inoculation of viruses of different degrees Pasteur alone knows, and he is constantly modifying, trying to improve his treatment and triumph over the opponents of his theory which he has many. Among them is an American, Dr. Stephans, who, in order to test his own theory, which is, that hydrophobia is “fancy bred” in man, never loses a chance of getting bitten by a mad dog. He has been wounded by canine teeth forty-seven times, and a German disciple of his, named Fischer, nineteen times. They are both perfectly well.

Let us enter the pavilion with Dr. Graucher. To the left of the waiting-room is the laboratory with hydrants on the white walls, tables with chloroformed animals and wastes from former dissections lying around. Here his recent experiment of putting little birds under a glass bell with diluted air were made. As soon as the little creatures entered they made few struggling movements, a few strokes of the wing and fell down motionless. A door from the laboratory leads into the yard with its stables, filled with horses suffering from glanders, and innumerable cages with rabid dogs, poultry, rabbits, Guinea pigs, white mice, etc., all ready for their destiny of being inoculated and vivisected.

To the right of the waiting-room is Dr. Pasteur’s office. It has, like all places about the pavilion, very much of a workshop air. The bookcase is a set of plain shelves, without even doors, and the portfolios on it are of the commonest sort. Other shelves contain retorts, tubes, phials, microscopes, vessels filled with blood, and hermetically sealed jars which are inhabited by millions of miasms. The tables are painted black.

Dr. Pasteur’s air is that of a grave old soldier. His bronzed complexion of a military veteran must have been inherited form his father, a soldier in the grande armee, as his own life has been sedentary. When he sometimes takes off his black velvet smoking-cap, which he always wears at home and in his laboratory, he reveals a solidly-constructed forehead, spacious and high without being arched. All the lineaments bespeak self-will and the habit of hard, patient and persevering work. A nose, that would be lumpy if shorter, is wrinkled in all directions at the bridge. A short, scant beard does not hide the massive, fleshy, and yet not heavy outline of the under part of the face. An air of thoughtful gravity pervades his countenance. But there is something of the African feline in the topaz-yellow eyes, which, when the bared head is thrown back, stare right before them into vacancy, as if to rest the optic nerve. One seldom sees eyes like Pasteur’s – sometimes lighted up by flashes of scientific inspirations.

A playwright would find much matter for amusing comedies among the assembled patients.

A story is told of a young lady whose loving but economical papa would not consent to take her on a visit to Paris. She, however, hearing of Pasteur’s inoculations saw in it a means for carrying out her desires. She got scratched, said the dog did it, affected terror and was whisked off from her native town in the Dordogne to a boarding-house near the Luxembourg. The truth only came out when she was in the crowd that awaited inoculation.

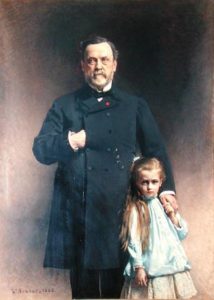

Gossip also tells of a South American millionaire who with the innate smartness of a Yankee, saw in a long-forgotten scratch in the face of a beautiful daughter a means of bringing her out in Europe with éclat. Knowing that M. de Freycinet was the intimate friend of Pasteur’s son-in-law, he visited the pavilion, and on hearing that no fee was accepted, subscribed a sum represented by four ciphers in a book, which appealed to the whole world, for a sum of f600,000 to found an institution for the prevention and cure of rabies. Next evening he and his daughter occupied the President’s box at the opera and were fairly launched into Parisian society.

After his office hours Pasteur lives entirely for new scientific explorations and his family. He has very strong family affections. There never was a more dutiful or kinder husband or father. And the members of his family are well deserving of such devotion, as they are not only cheerful companions but indispensable helpmates in his work. Mme. Pasteur comes from a pedagogic family; her name was Laurent, a French rendering of Lazarus. She and her daughter studied science so as to be able to aid the savant in his researches, and during a severe illness of his collected a good deal of the matter for his investigations of silk worm diseases.

At home Pasteur dressed carelessly in an old pea-jacket, on the breast of which the red rosette of an officer of the Legion of Honor is conspicuous. When he goes out his loose fitting clothes are as neat as a soldier’s on parade, and his boots as highly polished as the best blacking can produce. In taking constitutional walks in Luxembourg, his squatty figure is seldom seen without the company of a young disciple, or his twelve-year-old grand-daughter, on whose arm he leans, as he is threatened with total paralysis.

Pasteur’s ambition was to be a painter, but to please his father, who wished him to become a schoolmaster, and his mother who had a passion for book-learning, he took to science. A professor, under whom he studied at that time, turned his attention to chemistry. At this juncture a schoolfellow was given a microscope for a birthday present, which he allowed Pasteur to take with him on holiday outings. The instrument opened to him a universe, and eventually led him to take up the investigations of Swannerdam and Boyle, the discoverers of the domain of science, which Pasteur has so successfully explored.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing