Where do cells come from? If a cut of meat is let out, over time it will putrefy and begin to teem with microorganisms and possibly with larger organisms like maggots. Prior to the mid-to-late 19th century, the origin of microorganisms in decaying matter was in question. Some maintained that microbes arose from other microbes that landed on the food from the air. Other supported the hypothesis of spontaneous generation, which states that living organisms can arise spontaneously from nonliving matter.

Redi’s Experiment

In the 1600’s, Francesco Redi sought to test the hypothesis of spontaneous generation by applying what came to be known as the scientific method–a process of making observations, asking questions, formulating a hypothesis and designing experiments to test the hypotheses.

Redi and others observed that flies and then maggots could be seen around pieces of meat that were left out in the open. He therefore asked the following questions: Where do flies come from? Is the rotting meat transformed into the flies? From these questions, Redi formulated the hypothesis that only flies can make flies, and that rotting meat cannot be transformed into flies.

Redi sought to test his hypothesis by performing the following experiment. He placed pieces of meat into three glass jars. The first jar was left open, the second was covered with a loos netting, and the third was completely sealed. All jars were exposed to flies in the surrounding room. Redi predicted that if meat could not be transformed into flies, then the sealed containers should not produce either maggots or flies. Whereas if the meat can be so transformed, then the sealed jar should also develop maggots and flies.

Redi recorded the presence or absence of flies and maggots in each of the three types of jars. As he predicted, neither flies nor maggots were found in the sealed jars, whereas in the open jars, maggots and flies were abundant. In the jars covered with netting, maggots were found within the netting itself, but not on the meat inside the jar. Redi concluded that meat could not transform into flies, only flies could produce flies. The theory of spontaneous generation could not be supported and was therefore incorrect.

Pasteur’s Experiment

Unfortunately, Redi’s experiment did not convince everyone. Some argued that while spontaneous generation might not apply to larger organisms like maggots and flies, it might still be applicable to smaller microbes. The question was finally answered definitively in the late 1800s by Louis Pasteur, in his now classic experiment.

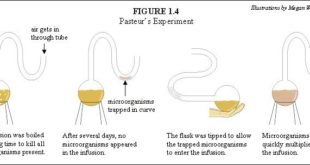

Pasteur’s hypothesis was that if cells could arise from nonliving substances, then they should appear spontaneously in sterile broth.

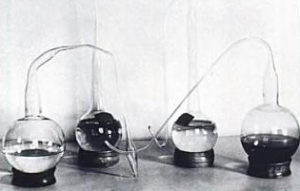

To test his hypothesis, he created two treatment groups: a broth that was exposed to a source of microbial cells, and a broth that was not. For his control treatment, Pasteur used a straight-necked flask that allowed particles in the air to fall into the broth stored in the flask. For his experimental treatment, Pasteur used a swan-necked flask. The neck shaped and length assured that no cells could enter the broth from the air.

By changing a single variable–the shape of the flask neck–Pasteur was able to conclude that cells were not generated spontaneously but were actually entering the broth from the surrounding air. Microorganisms, carried by dust particles, fell into the straight-necked flask. However, the swan neck trapped the particles, preventing cells from entering the broth.

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing

Pasteur Brewing Louis Pasteur – Science, Health, and Brewing